Every Three Hours Is A Chance To Make A New World: Notes from the Oklo Reactor

A brief pause in political doomscreaming to remember where we came from and how beautiful and powerful the science of stories and the story of science can be

Not everything has to be politics.

Some things are all-consuming fires from the primal depths of time and the void.

Last Friday, in my usual bleary, resentful early-morning delirium, I followed a link in the comments section of an article about something beyond completely unrelated to the treasures hidden by that blue text (oh, concerned piece about long-term effects of America's increasing marijuana use, who knew you came bearing such gifts!) and pitched headfirst down a long rabbit hole, at the bottom of which, somehow, turned out to be a molten ancient nuclear reactor I feel just unreasonably affectionate toward now.

Obviously I immediately went to tell the internet about it, which is REALLY NOT THAT EASY ANYMORE since I guess we've all just given up on APIs and cross-posting apps because billionaires hate nice things.

Problem is, I get SO FUCKING EXCITED about learning something new (and this one is a DOOZY), and then EVEN MORE EXCITED about teaching others something new, that it's all I can think about for several hours on either end, and I don't quite know what book I'm going to DEFINITELY USE THIS IN yet, and work still must be done while the child is in school, so...I want to expand on what I wrote on the annoying micro-blogging websites here, where I can use BOTH primate tool-usey wiggle-parts.

So this is the bigger, grander, more in-depth, more accurate, and more ADHD EXCITEBIKE version, all in one place and much longer, just for you fine folks who support me here and over at Patreon*.

*The nine o’clock show is completely different than the seven o’clock show disclaimer: This essay and the Patreon one are not quite the same, so that everyone on each site feels they got their money’s worth of something special**. (Only 96 paid subscribers left to commit to a biweekly posting schedule!)

**Plus I learned more in discussing it over the weekend.

Look, there's a reason I became a writer, well, many reasons, but one of them is definitely that it's a great way to just be in graduate school and writing a thesis all the time, because research thrills and excites and absorbs me like little else. That is extremely stressful. It is also extremely stimulating! Another reason is that being a professional writer is a fantastic way to force other human beings to love and care about the obscure, irrelevant-to-daily-grindlife things you love and care about. I literally get short of breath learning something new and fascinating, and then, sadly for all of us, also literally, run around spinning in delighted circles like Maria in The Sound of Music singing loudly to the hills so everyone has to listen to my latest nonsense. It's deeply embarrassing, and I feel sorry for my friends.

But THIS ONE is the coolest thing I've learned about in a hot minute--both adjectival puns intentional.

When I first started reading about this, I wondered if maybe this was a thing everyone already knew about and I just missed somehow. If so, WE CAN GEEK OUT IN THE COMMENTS. If not, WE LEARN/FEAST TOGETHER. But I gather from reactions (heh) to the initial thread that it's not terribly well known to the general public, so AHHHH LET'S JUMP INTO A LIBRARY AND COVER OURSELVES IN BOOKSMELL.

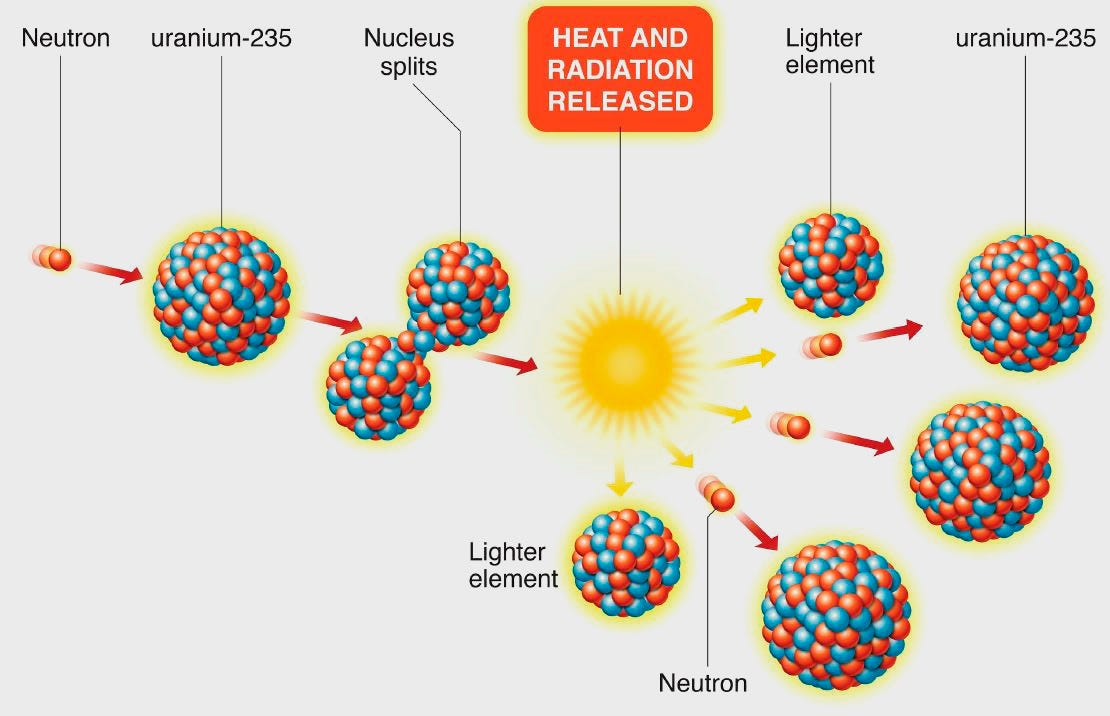

SO. It turns out that, under the precise right (or very wrong) conditions, large natural deposits of uranium can develop spontaneous nuclear fission chain reactions identical to the kind we make on purpose in modern nuclear reactors.

This has already happened at least once. About 1.7 billion years ago in Oklo, Gabon.

How do we know a spontaneous natural nuclear fission reactor formed in Africa 1.7 billion years ago?

Well, in 1972, a bunch of French chemists were quality-testing reactor-bound ore from Gabon, and it turned out a LOT of the local uranium was already markedly depleted, far more than any previously-found Happy Fun Rock, some of it by over 40%. Which meant, at the end of the day, this lab's till was short a whole lot of radioactive isotopes that should have been produced by processing that Gabonese ore.

This being the Cold War, people were pretty uptight about accounting for and tracking all fissionable isotopes in or out of any given civilian facility because, you know, big boom bad, so somebody was in trouble and they needed to figure out pretty quick how this could possibly have happened in a fairly new mine, or someone was going to get real aggressive about who stole the doomcookie from the doomcookie jar.

SCIENCE TIME.

Turns out the specific type of depletion in this ore told the story. In artificially processed and/or depleted uranium, the big players, U234, U235, and U236 are all affected. In the Oklo deposits, U235 showed the same type of depletion we find in spent waste materials left over from light water reactors. All the expected "product isotopes" and "daughter nuclides" that get churned up during fission reactions were present. But in our reactor waste, U234 and U236 are still present in small, altered amounts, because those isotopes are both consumed when neutrons merge and produced by fast neutron reactions happening during the fission process. So most of them get burned up, but the burninating process also makes more, so there should be some leftover at the end of it all, if not as much as the deposit started out with.

But in the Oklo materials, U234 and U236 were totally gone, because, you know, even at the crazy half-life of all this crap (250 million years, give or take), 1.7 billion years is plenty of time for it to fade to black. So this wasn't uranium humans had used to make anything go (reactors) or stop (bombs), it was ore that hadn’t been doing the VERY fiery splits for a long, long time.

The French team announced their findings: around 2 billion years ago, a self-sustaining nuclear reaction had occurred naturally within this pile of West African rock. And over the next many years, other sites, all near Oklo, showed the same markers, all part of the same extreme, widespread event.

It doesn't mean anything and it's not important, but it made me smile: that announcement took place on September 25th, 1972, which is my child's birthday, forty-six years before they were born.

So here's where it gets (more) interesting.

The Oklo reactor started doing its thing around 1.7 billion years ago, which is a very specific number. That puts it during the Paleoproterozoic era, when life on Earth was a loose gentlemen's club of sea algae and a few early eukaryotic cells. Before anything. Before dinosaurs or mushrooms or bacteriophages or even your mom.

Atmospheric oxygen was pretty damned new. It came from cyanobacterial photosynthesis...probably, and maybe a big comet or meteor hitting the Earth like Santa's gift bag, full of funkadelic outer space molecules.

Thus, the oxygen content of our atmosphere had only recently gentrified the joint & ticked up to a perky 2%, which is not perky at all considering our current atmosphere is 21% oxygen. DON’T JUDGE HER, EVERYBODY'S GOTTA START SOMEWHERE.

But Our Problematic Friend Uranium can only dissolve into water in the presence of oxygen, and the oxygen in water doesn’t count because, well, if you use that up it’s not water anymore. So all this uranium was lying around being a mountain and hills and ground, probably constantly inundated with groundwater for who-knows-how-long, until the oxygen in the atmosphere was thick enough to allow uranium to do what it does. The groundwater seeped into a uranium lode and moderated the neutrons being produced by natural nuclear fission into a self-sustained chain reaction just the way the rods & pools of a man-made reactor do.

Long story short? The Oklo reactor burned & cooled on a THREE HOUR CYCLE for HUNDREDS OF THOUSANDS OF YEARS until all the fissionable material was used up.

Yep. Three hours. Concentrations of the gases produced by fission trapped in the Gabonian ore fields allow us to actually know the time intervals of the reaction cycle from 1.7 billion years ago (which, what the fuck, we are amazing sometimes) and it's BONKERS.

30 minutes of mega-Chernobyl-style criticality that boiled away the Super Helpful lightly-oxygenated groundwater, then, once it was gone, without a moderator to slow the excited neutrons down (don't worry too much about it but there's a weird counter-intuitive thing where water cooling and slowing these neutrons is what makes the chain reaction stable enough to keep going, without it, the critical reaction itself slows down even though the neutrons are moving faster I DON'T REALLY GET IT EITHER) the chain reaction went through 2.5 hours of cooldown until the water could seep back in & the whole thing started all over again.

FOR HUNDREDS OF THOUSANDS OF YEARS.

So to recap, 1.7 billion years ago, when life was basically just Spicy Algae, there was an open, bleeding, unfathomably, incandescently hot wound, spreading for miles around curve-in bit on the west coast of Africa that ooze-ploded underground every three hours for several hundred thousand years, hurking out radiation, intense heat, & all kinds of xenon, iodine, caesium, & barium into the air, groundwater, soil, nearby sea, & very, very early photosynthetic organisms.

All this happened about 3km below the surface, which would seem safe enough shielding, except…that particular basin was once home to a shit-ton of geysers, unstable volcanoes, and still-antsy plate tectonics moving geography all around. Any one of these could have churned radioactive material to the surface, not to mention the possibility that the primeval geography was still very much in flux. Portions of the reactor may have breached the surface all on their own during portions of these hundreds of thousands of years of earth, sea, and everything else figuring out what they wanted to be when they grew up.

Now, I'm not remotely a scientist, but on reading about all this I immediately wondered if the Oklo reactors, and others, if they occurred elsewhere & we just haven't found them yet, alongside ultraviolet radiation, could be a pretty significant factor in Spicy Algae mutating into Spicier Bubbles & Piquant Fungi, and so on all the way up to us. Radioactivity doesn’t behave like it does in comic books, but it does create mutations when it doesn’t kill the thing whose DNA its shuffling like a shitty Reno card dealer whose favorite relaxation technique is meth. Most of those mutations won’t be useful or survivable, but some will, and will be passed on to the next generation, and the next, if they give anybody a leg up in the local environment.

See, 1.7 billion is a very neat number in terms of Earth's timeline: the evolutionary party started popping off not long after that. It would explain why so much of everything came from Africa and its extreme biodiversity despite lots of other fertile and temperate zones all over the place. It might imply reasons why the next earliest stage of life was indeed primitive fungi, mushrooms being things that spring up often in areas of high radioactivity because many can consume or otherwise process it.

A Primeval Splash Park of radioactive slag interacting with a few Floaty Cell Bois for hundreds of thousands of years, longer than all of what we would even recognize as human civilization has been around, slinging wrecking balls of recombinatory chaos into everything around it. Maybe all of us came from this Devil's Threeway of seawater, light, and magic rocks, slouching toward sentience, their hour come, well, maybe, someday, if we're lucky.

Maybe our mother is a stone in Africa. Maybe that's our home.

So I Googled it, & that was in fact the very next hypothesis made by actual smart scientists. QA techs may well have discovered the origin of life. This is a very real theory about the origin of the vast biodiversity of our Mutation-Happy Planet. Can we prove it? Not really. Are hypotheses that feel right and pretty and neat around the edges often wrong? Boy howdy.

And yet. Reading about all this felt almost religious to me. Which is the root of much misinformation, but we take what feelings of connection and purpose we can these days. Because not only all this *gestures wildly at the above*, but the glorious poisonous underground psychotic finger-painting that was the Oklo reactor was only possible because natural uranium deposits of uranium had much higher concentrations of U235 1.7 billion years ago than they ever would again. This could never happen now, not the natural fission of uranium or the groundwater reaction. Nor could it happen before it did, and very soon (on a planetary scale) afterward, it couldn't happen ever again. There was a tiny little window in which the deposits had enough U235 and the water was oxygenated just enough. Sure, a coincidence. Sure, a dumb-luck geological pimple-pop that may occur so rarely in the universe that life's apparent sparseness amongst trillions of star systems makes nothing but sense.

If God is a word you’re comfortable with, perhaps a way of thinking of such a force lies in the confluence of light, water, and stone, touched by the finger of time at just the perfect moment, then never again.

Maybe Plato was right, and those gods did split us all apart at the beginning of the world. Over and over again.

So whenever you feel like everything is terrible because mostly everything is terrible, remember that we are very likely just a runaway nuclear reaction that found a way to outlive its power source, get up out of the ground, walk around the place, screw everything up, make some really beautiful art, unscrew a couple of things, screw way more up even worse, have a lot of existential crises, leave the planet completely and venture out into the fucking stars, get bored of venturing out into the fucking stars, create sitcoms and pop music and Doric columns and fascism and religion and acid-wash jeans and musical theater and combustion engines and antibiotics and love and grief and hate and joy.

And also sometimes that ambulatory runaway nuclear meltdown became tigers or dragonflies or horseshoe crabs or bananas or the leather in a leather jacket or the hibiscus in an old lady's garden or a grey cat named Mystery limping up a strange human’s porch hoping for help, tomatoes in your salad or the General Sherman sequoia or your mother's piano or the olive in a martini or the pages of a book. It was dinosaurs for awhile. It was whales. It was Lucy, the little girl in C.S. Lewis's imagination or the skeleton in Ethiopia, and then it wasn't either anymore. The inferno even got fancy enough to figure out that it was a walking, talking, feeling, anxiety-riddled nuclear meltdown still-in-progress, and yet kept on going, on and on, out and out, more and more, maybe just trying to be, in aggregate, just a little better every cycle. On thirty minutes of real productive criticality every three hours. Every thirty minutes, another chance to escape a closed loop and make a new world.

And real talk, thirty minutes of actual productivity every three hours feels just about right these days.

So, honestly, it's okay to be a hot mess. It's what we came from. It's our birthright. It's our mother and father. It’s a miracle, if ever one has occurred. And it's beautiful, even as it's terrifying. It's us. An endlessly cycling fission event and all its horrifying, glorious byproducts, all confined in the bodies of trillions of organisms. We are all one. It's just that the thing that unites us is a catastrophic vivisection-by-flame of our every cell and deeper still, which really makes everything make so much more sense, when you think about it That crack in the Earth up there is a picture of Mom. Mom did her best. Sometimes your kids get away from you. Sometimes they don't call. The molten stone of the beginning of us is still inside, all the time, and it's just chemicals and minerals, it doesn't know or understand why your marriage didn't last or you lost that job or why dinner out is so stupid expensive now or who will win an election. It's just fire. It wants to burn. It wants to warm. It wants to move.

It wants to grow. It wants to breathe, and to live.

I think we've all done extraordinarily well for a bunch of broken, wet, rocks slowly cooling over eons in the middle of a void.

I think you've done amazing, sweetie.

And so did Mom.

oh my god that's GORGEOUS, Cat

thank you

I remember seeing that in Scientific American and being absolutely enchanted by the idea of a natural fission reactor. What fascinates me the most is how negative feedback loops kept the reactor running within fairly narrow parameters, almost as if there were an intentional operator at the controls. A few years later I fell down the rabbit hole wondering if that could have happened elsewhere and -when as well. Couldn’t find any definitive answer because the tendency is to dig the uranium out of the ground and make either reactors or bombs out of it as fast as possible, and damn the measurements.

One thing that reactor can teach us is how to contain fissionable material, whether fresh or depleted from use, for long periods of time. That reactor ran for thousands of years without a meltdown. And countries other than the US have been successful in storing radioactive waste safely. For us it’s a political problem, not a technical one.

“This being the Cold War, people were pretty uptight about accounting for and tracking all fissionable isotopes in or out of any given civilian facility because, you know, big boom bad,”

And yet Hanford has admitted they can’t account for more than 1 metric ton of plutonium (more than enough to make 50 Hiroshima-size bombs). They don’t think it’s actually gone walkies, just that their process is imprecise. Then again, they sure left a lot of high radiation garbage lying around. This is a bit of a concern for me since I live in Portland (Oregon, not the one near you) just down the Columbia River from the creeping crap that’s leaking from Hanford.

All of which makes me wonder what an archeologist of some intelligent species evolved after we’ve been gone for 10 million years would make of the isotope ratios in the ground around Chernobyl.